I’ve been working at the internal platform team at Mercari for 3 years. In that team, we’ve developed and provided the special Terraform module, which bootstraps required infrastructure and SaaS services for building one microservice, to internal developers (See more details on Terraform Ops for Microservices). Now, this module is used by more than 400 services (since we create both development and production environments, actually it’s 800) and we’ve released the module more than 30 versions.

This blog post introduces some of the practices we developed while working on that Terraform module. "Better", in this context means, from the module user’s point of view, easier to use and easier to maintain for a long period of time. Since the practices are very high level, some of them can be applied not only for the internal Terraform module but also for the public one and other software development like Kubernetes CRD and so on...

On Design

When designing the Terraform module, the first and most important thing you need to aware of is the variable of the Terraform module is API. Once you define a variable in your module definition, it’s open to users and target to modification. This means it becomes an interface between users and your module. In this sense, you can think of it as API.

Since it’s API, what kind of variables you define decides the complexity and the usability of your module. But, fortunately, many practices have been developed for good API design in this industry. The followings are some of the practices from them and I think it’s important for Terraform module design.

Module should be deep

The Terraform module is an abstraction of the collection of the raw Terraform resources. An abstraction, in general, is a simplified view of any entity, which omits unimportant details. We create a module to make it easier for your users to think about and manipulate complex resources.

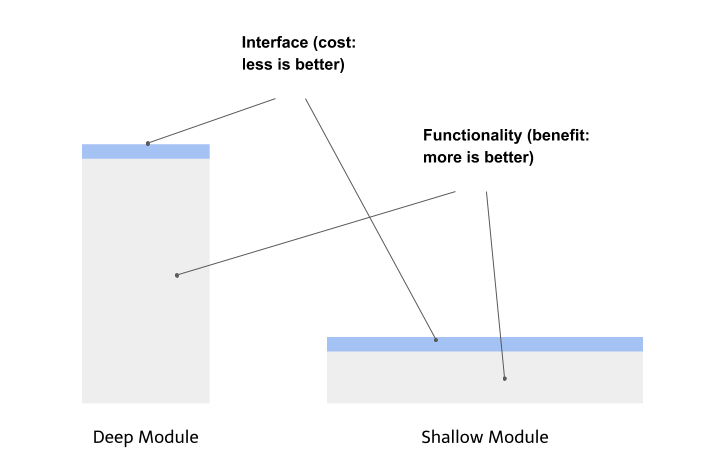

The best modules are those that provide powerful functionality yet have a simple interface. In the book, A Philosophy of Software Design calls this "Deep module" (The word "module" is used for different context and not about Terraform module but you can think of them same). You can see the visualized notion of this above. "Deep" means they have lots of functionality hidden behind a simple interface. On the other hand, “Shallow module” is one whose interface is relatively complex in comparison to the functionality that provides (does not hide much complexity).

The module’s interface represents the complexity of that module imposes to the user: the smaller and simpler the interface, the less complexity that it introduces. When designing your Terraform module, always think about the depth of it.

Be careful that once you open your interface and it’s used by users, you can not change or delete it easily. And it may be used in an unexpected way (See Hyrum's Law). So what variable to expose is really important.

You can more learn about interface design from e.g., Consider the interface.

Interface should be intuitive

The module interface = variable should be intuitive to use. What happens when changing the variable should be obvious and predictable to your users. Don’t surprise your users. For example, avoid using the enable_x variable for enabling features not related to x.

Using consistent naming and format in the same module is also important to make it intuitive. For example, if the module uses the enable_x variable for enabling feature "x", then enabling "y" should be also done by the enable_y variable, not by setup_y or use_y.

Variable should have smart default

The module variable should have a smart default value which covers 80% of users. The smart value means the best value in a limited context. The module which can be used without any configuration is the best (It also related to the upgrading strategy below). You should design carefully what default value it should have.

But, at the same time, it should have configuration knobs for the power users. Normally, you have the power users who can not use the module like the 80% of normal users. For such users, you should prepare ways of changing the behavior of the module. This knob should be designed properly and avoid having a shallow interface.

On Upgrading

Upgrading is one of the most critical tasks of long-developing software. But, at the same time, it’s also the most bothering task. This is also true for the Terraform module, especially which is for the general purpose and widely used... It's been huge problem for our Terraform module, too.

Since normally new features are added to the latest version, if you want your users to use the feature, you need to ask them to upgrade it. To make it works, upgrading must be easy as possible and less cost to users.

To make upgrading easy, keeping backward compatibility is most important. In the case of the Terraform module, if there is no Terraform state diff when upgrading the module version, it keeps backward compatibility. If there is no state diff, users do not need to care about anything when upgrading. So the best upgrading is no Terraform state diff.

The following practices are the idea of achieving this and reducing the cost of upgrading.

New functionality should be off by default

If you want to introduce new functionality to your module, you should make the feature “off” by default. It should be explicitly “on” by the users who want to use it.

Sometimes, you want to enforce all your users to use some features by default. Even in that case, you should do it gradually. When introducing, it should be "off" by default. Then you should ask users to enable it explicitly. After the feature adaption rate is increased (you should monitor it), then you can make it “on” by default. With this, you can reduce the effect of upgrading.

Upgrading should be automated

In other words, prepare dependabot for your module. Especially, if you update the module frequently, you must prepare it. Even if you ask your users to upgrade, normally they don’t work on because normally they have more important tasks to do. We struggled with this a lot. So, instead, create PRs for them.

Internally, not only we send PRs of new version upgrading, but also we have the mechanism to automatically merge the PR if there is no Terraform diff. With the combination of this and keeping backward compatibility practice, we can increase the rate of users who use the latest version of the module.

State diff should be small as possible

It’s not possible to make upgrading no state diff always. Sometimes you need to introduce breaking changes e.g., because of changes in dependent resources or security issues needed to be patched as soon as possible. In that case, you must think about how to reduce the cost. If the state diff is less, then the cost of upgrading is less. The more you include diff, the fewer chances users upgrade it.

When introducing the breaking changes, you must tell it by the documentation. The documentation can be CHANGELOG or your user guides. If the documentation clearly describes the changes or the actions users need to take, the cost of upgrading decreases. For example, if the documentation shows what kind of state diff is expected in the documentation, the users can upgrade it without fear.